- Home

- McElroy, Joseph

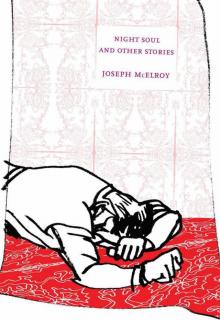

Night Soul and Other Stories Page 3

Night Soul and Other Stories Read online

Page 3

Teacher had been home-schooled herself. This Ali confided the day before the two men, certainly not parents of this school, were waiting when school was done and kids were visiting their cubbies before going home but Ali did not and turned a corner into a hall that led to auditorium, cafeteria, and side exit because he had seen the men show their wallets to Mrs. Molesworth and for a moment she looked across at Ali.

So it is she.

But still I ask him what school he attends and what grade. Still I want to protect him. There is too much information on the table already. It’s another job, not poetry.

His teacher is my wife.

She had been home-schooled in California long before she ever came east.

I was waiting for the right job. I told Ali that in 1982 we had achieved the highest unemployment rate since 1940. 10.4% on November 5th. 10.8% before the end of November.

With over eleven million unemployed. A dream like numbers odd and plain, and a song of crunching of teeth or a hand squeezing brown paper.

But out of work you can do what you like then, said Ali.

Today we could visit Brooklyn Bridge, he said one day. Big brother Abbod wanted to borrow his camera, so Ali would like to take some pictures first.

She tells me the questions. A kid went home and told about Mrs. Molesworth’s class. Her nomad class. We laughed, my wife and I, and almost loved it but loved each other. This mother has been given enough grief already by the hand she was dealt but her younger son made a nice comeback from lymphoma, and while he keeps an eye on the black kids in his class, picks up their jive and trash, this “dead presidents” stuff meaning folding money—city kids you know—he also hears that some crazy Arab cousin of a Muslim kid is headed for America? Hears Ali guarantee that a cockroach can help track bombs (?). “How do you know this?” the two men will ask Ali, the day after they’ve first questioned his teacher. He had read it.

No you didn’t.

Oh yes: in a magazine on teacher’s desk.

They know where the family lived previously, and that one son was thought to be living with them but has been seen leaving what was thought to be their former apartment house—“In Astoria,” the boy fills in. They’re about to go on but don’t.

Why did Ali come to school, having seen the men the day before?

“Welcome to Paradise,” a Green Day song he—

His family hadn’t yet been visited, I thought.

I found them in my wife’s address book plus lavash, flatbread recipe.

Ali’s teacher is my wife, has submitted to questions. Only then did she think to phone.

I know him, I tell my wife. The camera, she says. Of course, you gave him that old camera…Their minister said Ali has mouths all over his body. Their imam, I said. One of them, my wife corrects me.

On the Brooklyn side at first, the tiny park with the ducks—from under the Bridge shots of scale itself, pieces of it huge, mobile like history or dream, another piece, another like a ledge or barrier in midair, the Bridge in pieces, Ali an eye for the frame adjusting his aim by an inch or two, unaware of cops and others with the cops observing but not approaching, though aware that the man with Ali knew what was going on. They had us under surveillance when we were walking the Bridge and the boy taking the arch, the cables, the three-lane roadway below on each side coming and going, even the steel support structures one would be able to climb to get to or from the roadways but why? He was lending the camera to Abbod tomorrow and wanted…to…Wait, he murmurs…breathless…Wow—Absorbed, thoughtful of time, too—not of spectators behind us—they didn’t want us (or maybe me)—

My timing excellent. Seasons sometimes like minutes if you’re ready.

—then on the Manhattan side where the downslope bends around toward Chambers, police apparently waiting, a pale mist of rain adding its history to the boy’s. A regular hero? A fighter. For me to save?

Abbod? I said, surveying The Bridge I know pretty damn well.

Tomorrow you’re loaning him your camera…?

“Your big brother,” I say. American flag at top of a cathedral arch. Mmhmm, Ali half-acknowledges me as he focuses—I’m always an authority of some kind, I glance past the police a hundred yards away to a sign down on the roadway and its stream of cars: Dry Standpipe Valve for FD use only—while my boy up here on the pedestrian walkway is framing someone for a shot, or waiting for them to step away from a metal trap door in the stone underfoot for Repair Access. “Only half a brother, if you ask me,” I let fly.

“Know what he said? ‘You didn’t call on me when I was going to tell about caves along the river.’ He’s mad at me, my wife said. Next day he wasn’t in class. He knows how to cook. We should take him camping.”

Arriving at their block in Newkirk as if I didn’t know what else to do the day after he didn’t come to school—was he at large, was I?—before a guy in a windbreaker saw me down the street and spoke into his phone as the street door popped open like a lid and a man I felt I should know broke free of another and another and the cop phoning moved to intercept him like a strong safety between him and the goal line.

What is my job? To see what a child is seeing.

Ali—I thought of him, if I could save him, but from what? And there he is in the doorway when his uncle—for how did I know it was that irritable, nephew-loving atlas of learning long-legged, a fugitive back home where life at noon like mission accomplished might cost nothing to cancel—swerving off the cement path toward a lone forsythia bush fell headlong tripped up it seemed by a pistol shot’s synchrony and slow-legged into silence as natural as anything?

Police officer killed in line of duty, a news photo of him posted near the B and Q trains, near Ali’s apartment house, near the bus stop. Ali took the bus home.

I waited at the game store.

Once he said, “What do you advertise, Mister Mo?”

MasterCard Glueguns, Digestive Bombs, little yellow plastic teardrop containers of lemon juice. A driving school concern with agencies in Jersey and Maryland.

Asked about his home-study Qur’an, “Jesus didn’t have a father,” Ali replied as if I had asked. Would I have saved him from running to his uncle? From his mother’s scream? From looking up from his uncle shot down to see me near and have to decide what to do even about me? Which was nothing but to ignore me, his friend who doubted Abbod was a good half-brother. When neither the officer who shot his uncle, nor the other with him, nor the plainclothes with the cell, tried to question me.

Abbod had ID in case he had to show it but never had to until he volunteered it at the driving school and was given training even before they checked him out.

Routinely suspect, these people work almost as hard as our Koreans.

“Faquir” (?) a poor person. I waited at the game store.

I had known this neighborhood as a child, a grandchild. Things you know, all over the place. I told you I wanted a poet, she replies, meaning me.

Who were these nomads? These Scythians and other ancient minds. A dual-control driver training car found parked in Astoria sniffed stem to stern by a police dog, a half-empty red Classic Coke can in back with a half-smoked cigarillo awash in it, but certain grains of unburnt powder evidently cleaned from nook and cranny of firearm with compressed-air spray gun commonly used to clean computer keyboards.

Rendezvous though with a wife who likes the things you know and half-know (mostly half)—the ocean weathers, the laughter of Herodotus at map makers who would make Ocean a river running round a circular earth—yet his praise for Solon’s rule that every man once a year should declare the source of his livelihood at risk of death if he can’t prove the source an honest one.

Winds across the water, which hardly gives way…the Narrows…the Verrazano…My head adrift with bridges, we dream along a reach to converge far out at sea where on station a Coast Guard weather ship will plunge onward in a twelve-mile-by-twelve-mile square…

To go from thing to thing, not too afraid—knowing t

ruth has a better chance to trespass sudden and interrupting…

The Bridge in pieces and angles of itself—adrift like our seasons.

“Mister Mo.”

Mo thinks of what it is his wife wants. To travel. More than anything. She pores over a map of Asia. We make decisions together, don’t we? What is a map? I think I actually asked her. We’re still young, she not yet thirty-seven. (Home-schooled in California, when she grew up she had understandably come east.)

I must read only children’s books (Mandelstam writes),

Cherish only children’s thoughts,

Scatter all big things far and wide,

Rise up from the deep-rooted sadness.

I know what he means, but…

Employment: that’s number one right now…

What is my job? The future. Helping this boy…

“I know who you are,” Ali said, standing at such a distance that I stopped trying to close it, his uncle bleeding at his feet, arms fallen apart, his mother joining Ali distraught and then seeing me, seeing me retreat.

…a poet who died in prison: to be scattered through this history.

To go from thing to thing unafraid, that’s all: knowing the truth has a better chance sudden and interrupting or may come round again.

…pasturing your life…

New nomad waiting for it to come to me…

For nomad is the movement of others from me as if it made little difference who was the mover.

I did not need to die in my own country; and then I did not die at all.

Close, she said. She and I, she meant. She said Ali would speak without raising his hand—like you, my wife said. Has it come to that?—and once she failed to recognize him when he did raise his hand. She understood that I missed him.

He knows Ska, she informs me fondly.

Nomaderie nowadays. Did she get that from me? You could get into a state about it. You didn’t need to go anywhere anymore: it came to you, though nomaderie…A writer pausing at a village in Crete: “total absence of anything approaching a communal existence. We have become spiritual nomads; whatever pertains to the soul is derelict, tossed about by the winds like…”

A woman to whom I confessed comes back for more, having half-heard. For nomad is the movement of others from you as if it made little difference, if I could ever tell Ali this, who’s gone now.

Salat, five-times-a-day prayer.

We serviced the sites on a seasonal basis until the seasons began to come to us which would have made the job easier but the seasons changed in nature, pushing out from within: we were on the move but much more regular than our friends who stayed put; and the sites were everything you would have expected of a site, manned, unmanned.

Time we break into seasons briefer and briefer now like space where we are restless and think ourselves on the move. Until, having pulled the seasons along with us we turn to one long season its length no longer long or relative, no longer even length.

Seasons don’t wait for us but come along in us now and also speed away from us. I try, clocking in on my own (timeless, I hoped) job, to build on others’ work, John Clare’s “I Am”—“the vast shipwreck of my life’s esteems; / Even the dearest, that I love the best, / Are strange—nay, rather stranger than the rest.”

The nomad state: nomad nation.

Nomaderie, the form of “pieces.”

I believe the boy was in the end blamed for telling about his shepherd cousin.

I recalled my lost father largely self-taught reciting Emily Dickinson years before I knew who that was and as if she—for me now a foundling spirit, Founding Mother—were a card-carrying Christian: my father, a job printer on Vanderbilt Avenue near Grand Central, urging me to close the Arabian Nights, a tale of two unexpectedly linked dreams, as it happened, and open a book of fact, yet speaking to me as I to Ali like an equal.

Your God as a nomad.

I did not need to die in my own country; and then I did not die at all.

A woman who knows what to overlook yet seems to have overlooked nothing, was my thought about my wife, her map of world foods she discussed with her children.

I thought I would move on. And the boy. Abbod’s photos of the Bridge may as well have been the American dream left in New York when he slipped back over the border into the Notre Dame mountains by canoe, the long, eastward slanting lac a minute flattened ellipse in uncle’s atlas. “Abbod,” the mother said. “Abbod.” Strapping specimen with a hernia needing attention and some overdue dental work.

I know you, don’t I? the proprietor greets the boy who appears in his store one day in May or early June—used to go to school around here. You’re Ali? The boy squints, uncertain. You’ve come for your…Here, your friend ordered this for you. Green Day? What friend? asks the man with him, his arm in a sling, a Band-Aid on his nose.

The boy had accepted his gift. What was mine? About music, he had said, “Go for the Gold…lots of dead presidents, man.”

And so as season tried to follow season, severaling a various year to leave us breathless with travel excitement, sinus tumors in the healthiest and temperamentally richest of our loose group, with a late-developing sixth-sense problem and far away Down Under cancer cells proving contagious in an animal the name of which we will recall…war ongoing, a shepherd arriving…

THE MAN WITH THE BAGFUL OF BOOMERANGS IN THE BOIS DE BOULOGNE

He was not to be confused with my new friends or my old. He was there before I found him and he did not care about being discovered. I knew him by a thing he did. He threw boomerangs in the Bois de Boulogne. If he heard any of my questions, he kept them to himself. Perhaps we were there to be alone, I in Paris, he in the Bois that sometimes excludes the Paris it is part of.

But what makes you think Paris will still be there when you arrive? inquires a timeless brass plate embedded in the lunch table and engraved with an accented French name. Well, I’m in Paris, after all; that was obvious even before I sat down with my friend who invited me to meet him here, though the immortal name I put my finger on, that frankly I don’t quite place, might have been instead that of the burly American who’s also, I’m told, here somewhere staring in brass off a table—far-flung American name once commonly coupled with Paris itself. So now, like a memorial bench in a park, a table bears his name, that fighter who once clued us all in that you make it up out of what you know, or words to that effect. His pen (or sharpened pencil) had more clout even than his knuckles.

What is the name of that famous burly writer who lunched at this consequently famous restaurant? Out there past the brass plaques and dark wood surfaces and the warm glass and the conversation, the city doesn’t happen to answer. Not a student descending from a bus; not a woman hurrying by with two shopping bags like buckets; not a man in the street I’ve seen in many quarters carrying under his arm a very long loaf of bread and once or twice wearing a motorbike helmet. He is probably not the man my French friends patiently hear me describe, who is my man in the Bois whose very face suggests the projectiles he carries in a bag, a cloth bag I didn’t have to make up, to contain those projectiles in the settled November light of late afternoon in the Bois when I begin my run.

Which man? The man with the bagful of boomerangs, wooden boomerangs one by one, old and nicked and scraped and shaped smooth to the uses of their flight, one or two taped like the business end of a hockey stick. When I arrived, coming down the dirt path toward a great open green, and broke into my jog, he was there. And he was there when I wound my way back three or four miles later, in later light, around me the old cognates of trees, of dusk, of leaves, crackling under foot. Yet, veering down hedged paths, past thickets where dogs appear, and piney spaces with signs that say WALK, to surprise a parked car where no car can drive, and across the large, turned-over earth of bridle paths, and around an unexpected chilly pond they call a sea, a lake, that has hidden away for this year its water lilies, I could sometimes lose myself with the deliberateness of the pilgrim runner who

se destination is unknown and known precisely as his sanctuary is the act of running itself. So I find I am beside the children’s zoo, or so close to some mute lawn girdled by traffic thinking its way home that I can plot my peripheral position sensing I am near both the Russian Embassy and the Counterfeit Museum. Or I can’t see Eiffel’s highly original wind-stressed “tree” anywhere, whereas here’s a racecourse that I know, so now I must be running in the other direction toward Boulevard Anatole France and the soccer stadium. But I am still meditating the famed water jumps of the other racecourse, and turning back in search of the Porte d’Auteuil Metro, I breathe the smoke of small fires men and boys feed near the great beech trees.

But most often, I ended where the boomerang-thrower was working his way into the declining light. And passed him, because that was my way back to the Metro. He began low, he aimed each of those bonelike, L-shaped, end-over-end handles along some plane of air as if with his exacting eyes he must pass it under a very low bridge out there before it could swoop upward and slice around and back, a tilted loop whose moving point he kept before him pivoting his body with grim wonder and familiarity. As I came near, I would not stop running but I might turn my head, my shoulders, my torso, to try to follow the flight of the boomerang. More than once I felt it behind me, palely revolving, silent as a glider and beyond needing light to cross the private sky of the Bois, which for all its clarity of slope and logical forest is its own shadow and contagion within a metropolis of illuminations balconied, reflected, glimmering, windowed in the frames of casements. More than once I saw the boomerang land near its intent owner, wood against earth. Sometimes he seemed to be launching the whole bagful before proceeding to retrieve. What was his method? He would pick one boomerang up with another or with his foot. One afternoon I must have been early, I was leaving as he arrived; I wanted to know how he started doing this, because we had boomerangs in Brooklyn Heights before the War in a dead-end street looking out from a city cliff to the docks and New York Harbor and the Statue, and we hurled our pre-plastic boomerangs out over the street that ran below that cliff and thought of nothing, not people below, not the windows of apartment houses. I looked this foreign boomerang-thrower in the eye, his the angular face of a hunter looking out for danger, a blue knitted cap, old blue sweatshirt with the hood back like mine. What was he doing off work at four? The things in the bag were alive, their imaginary kite strings resilient.

Night Soul and Other Stories

Night Soul and Other Stories